Ideation

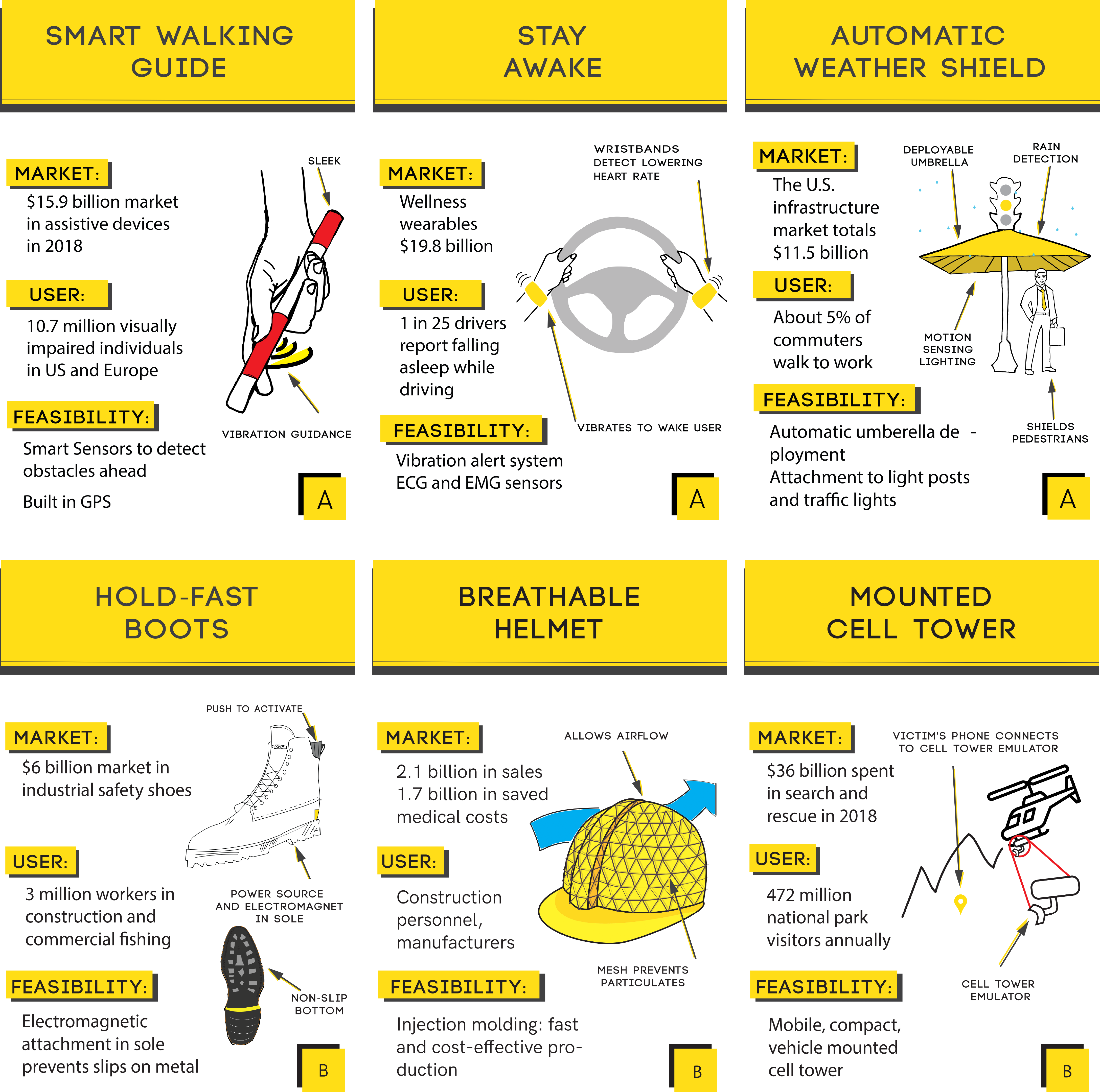

The first phase of the class was focused on ideation. Our team was split into 2 competing sides making as many ideas as possible. We pinned them up, evaluated pros and cons, understood market sizes, and discussed technical feasibility. After coming up with over 400 idea sketches, we pared down ideas as we built prototypes. The first phase was called 3 ideas. Each half of our team presented three ideas and their market sizes. I was out of town for this week but one of my original ideas, hold-fast boots was chosen as one of our 6 ideas.

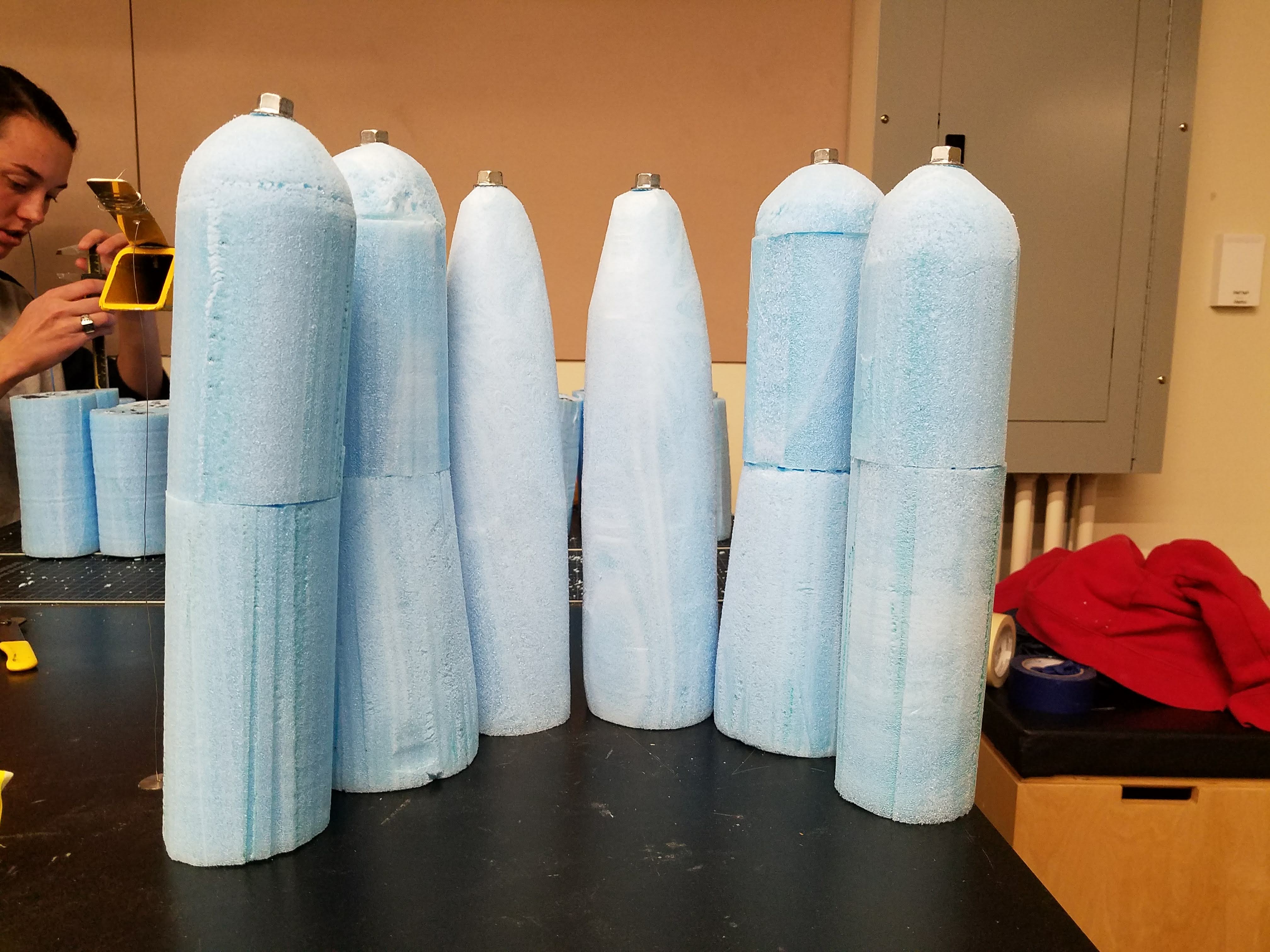

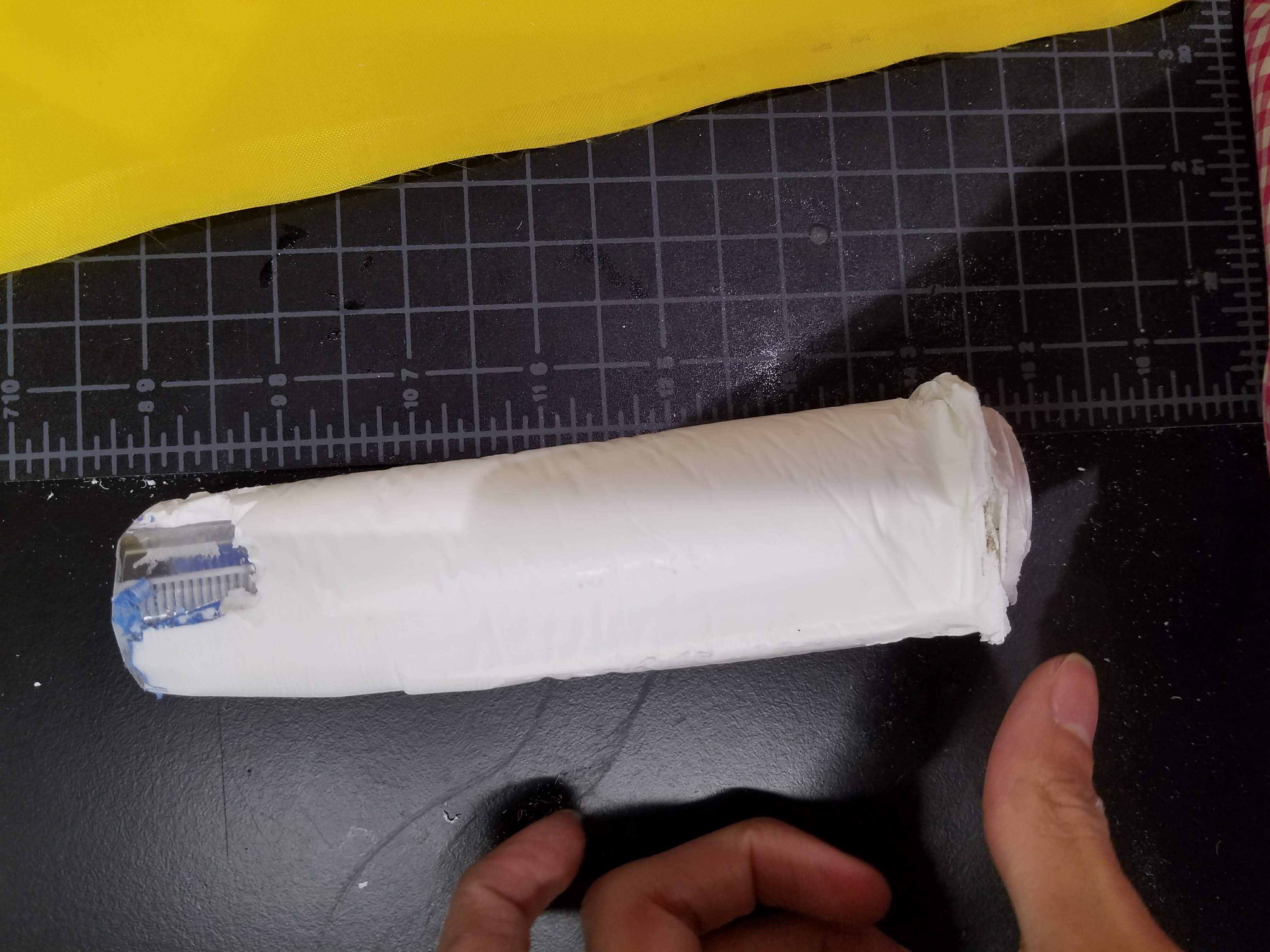

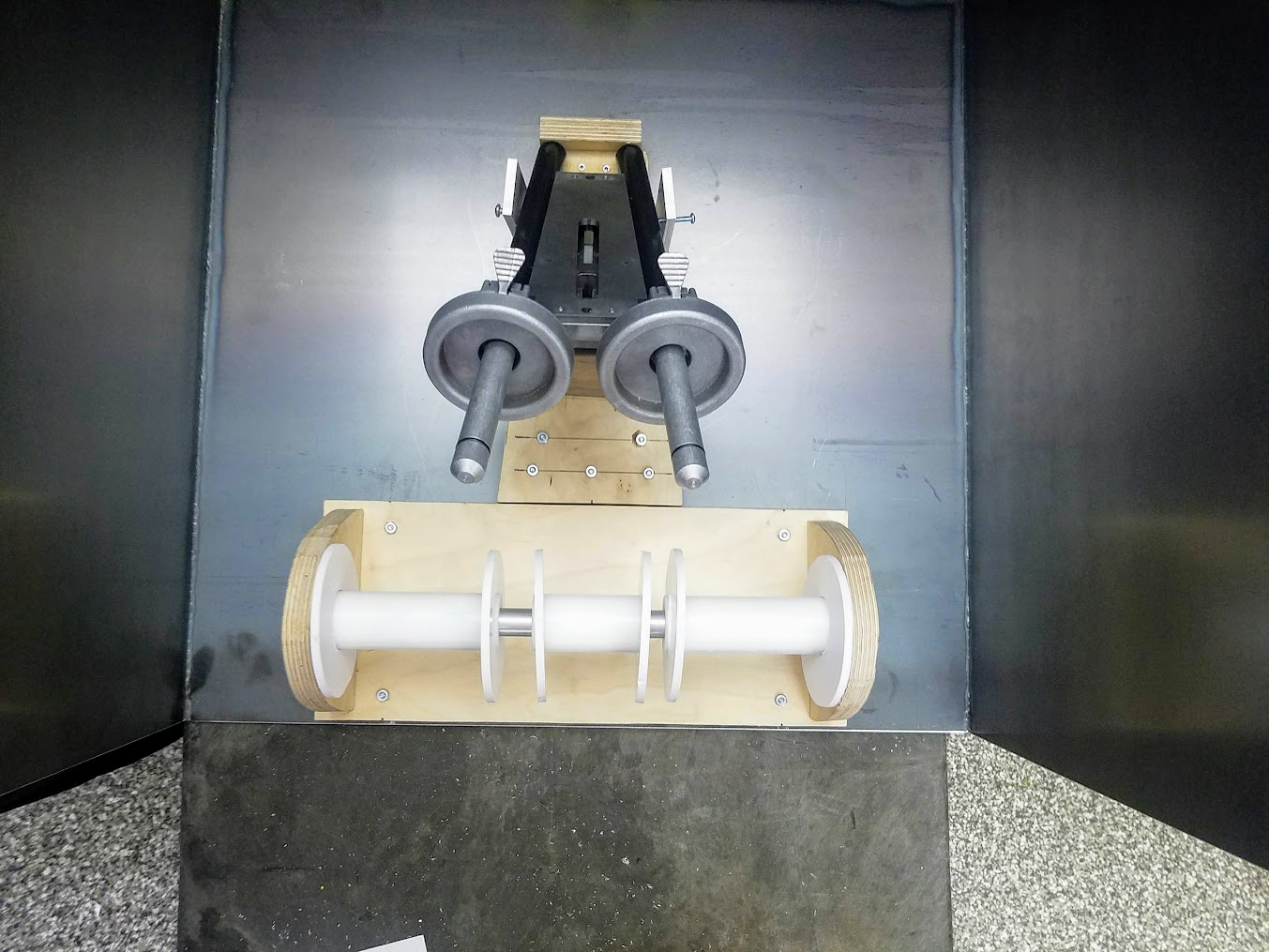

The second phase was the sketch model phase. Each half worked on simple hacked together prototypes. I had been focused on the hold-fast boots for which we built several prototypes. Commercial fishermen have one of the most dangerous jobs in the world mostly from falling into the sea due to rough waters. We wanted to mitigate this by anchoring the fishermen to the boat. We evaluated methods of adding traction to the boots by adding rubber suction cups, velcro, and an electro-magnet. We molded foam undersoles that would add suction, added an electromagnet to a boot, and added industrial velcro to another boot. After testing each of these, we found that prevention of falling is very difficult especially without harming the user. Additionally fishermen rarely adopt safety products, making it a very difficult market to enter into.